Politics

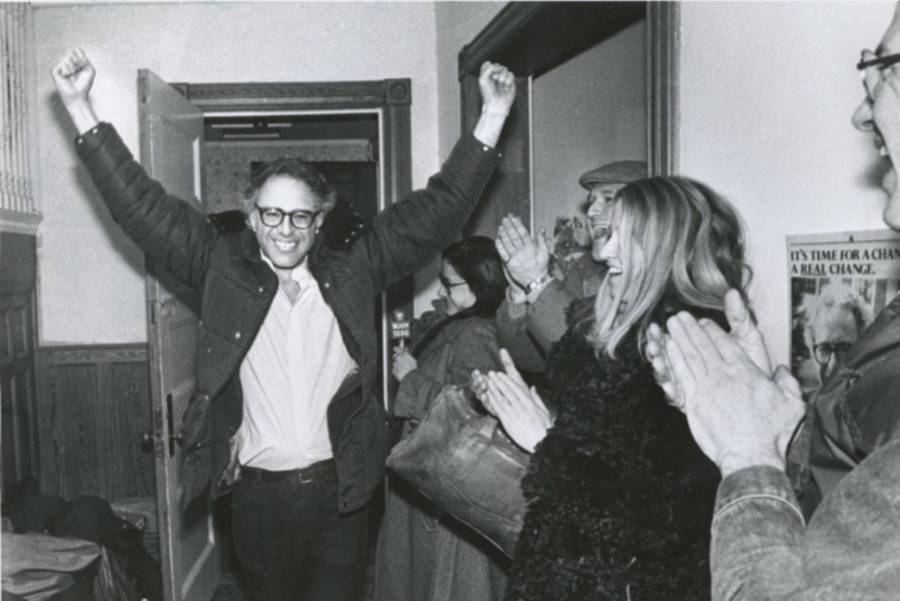

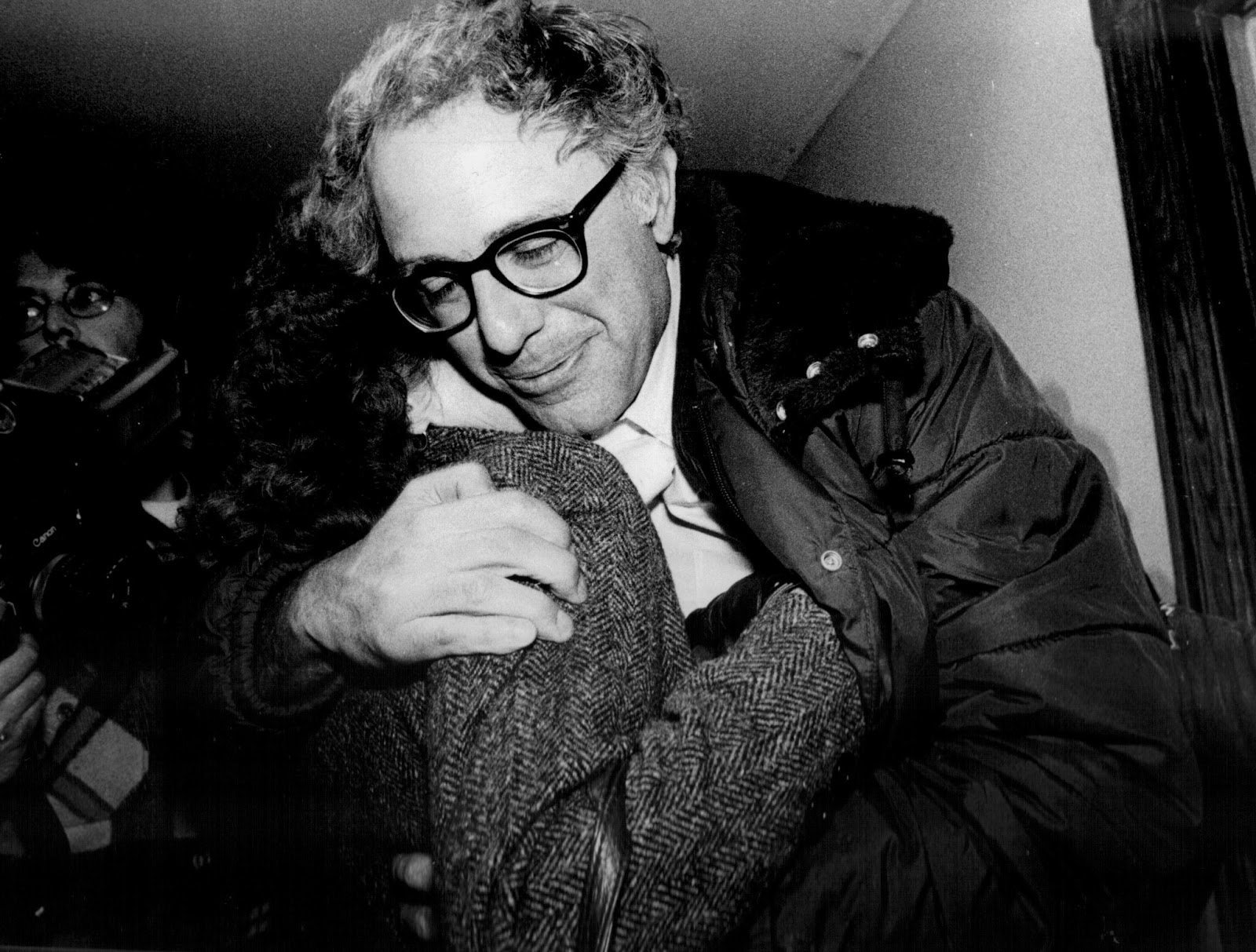

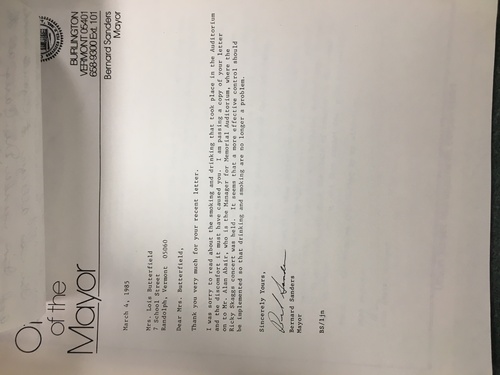

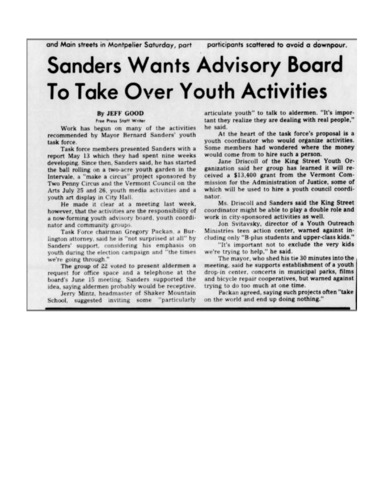

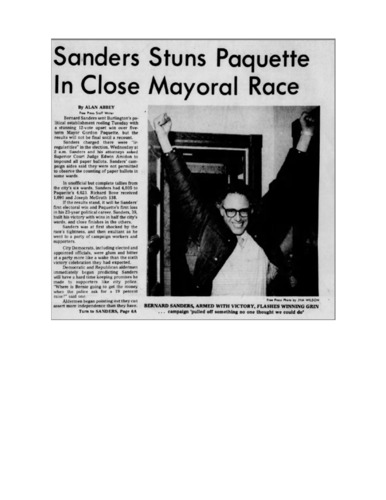

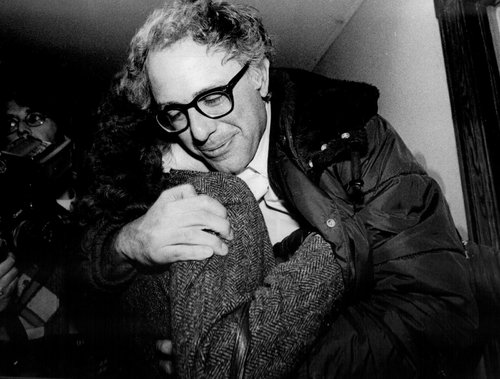

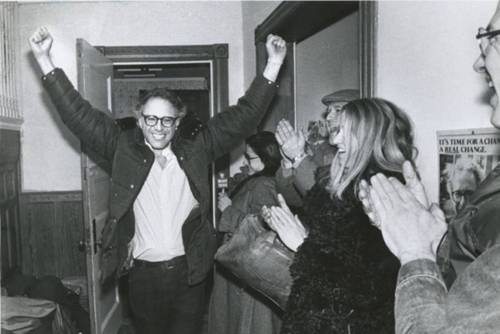

Bernie Sanders became Burlington mayor in a shocking upset over five-term incumbent Gordon Paquette on 3 March 1981, securing his first electoral victory with a margin of only ten votes.[1] The campaign had been difficult, the election ultimately bolstered by a surge in volunteers as well as a series of endorsements from university professors and the police union.[2] The city’s political establishment reeled; few had expected a relatively obscure newcomer to pose such a formidable challenge.[3] Within days of his election, Sanders began to work toward fulfilling his campaign promises. To this end he formed a youth task force—led by Burlington attorney Gregory Packan—to recommend new recreational outlets for the city’s youth. The task force submitted a proposal on 13 May. It called for the appointment of a youth coordinator to organize the devised activities.[4] Jane Driscoll became the unpaid, full-time volunteer youth coordinator soon after. On 30 July 1981, five years after then-Mayor Paquette first proposed the idea, a youth office officially opened in City Hall.[5]

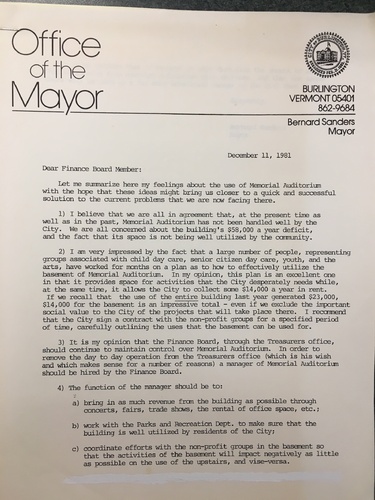

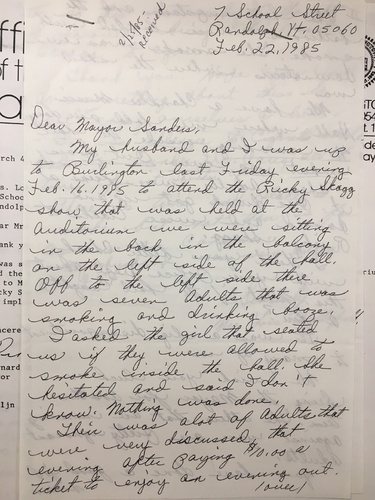

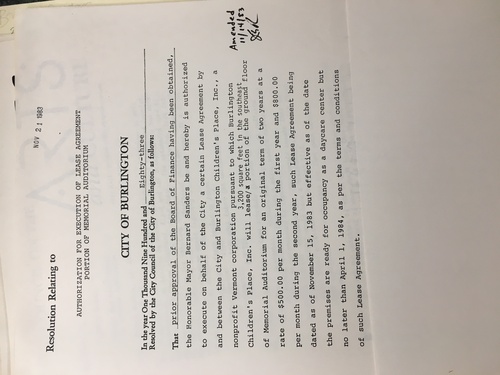

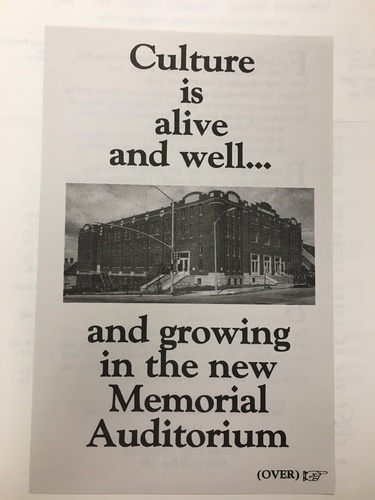

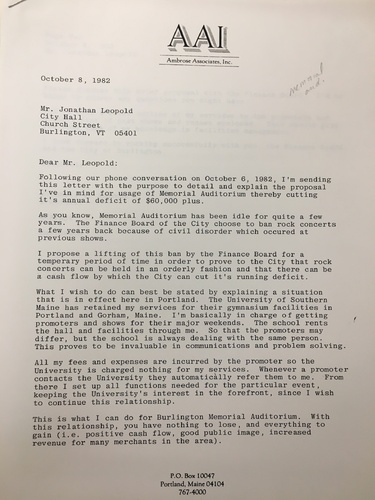

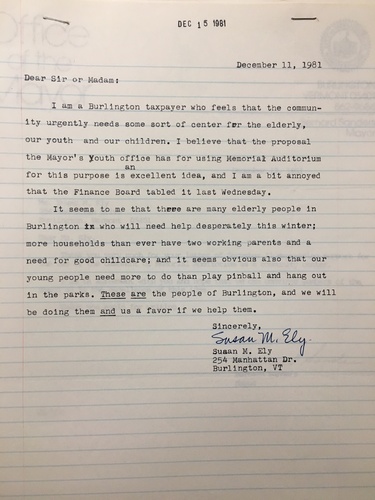

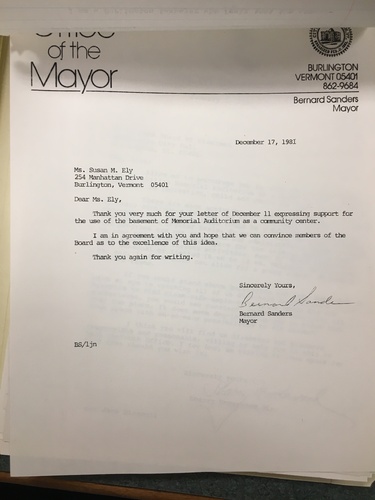

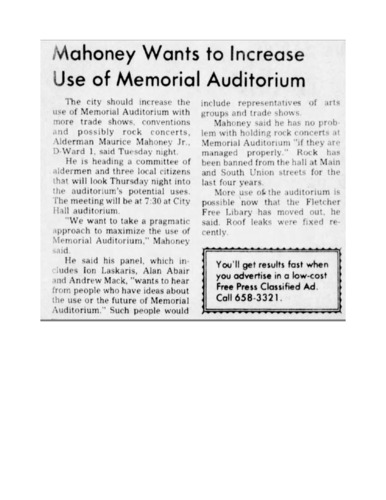

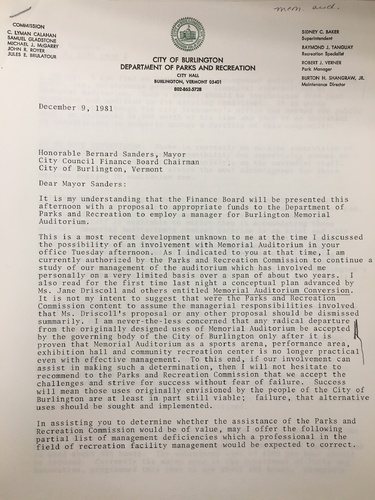

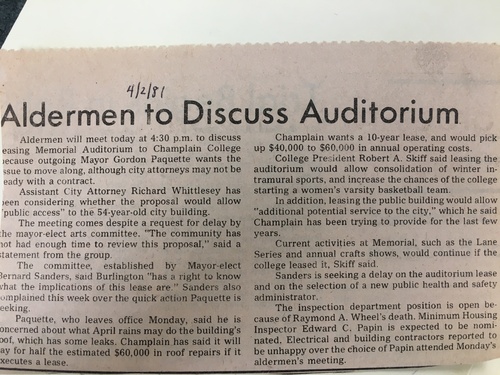

Among the pressing political concerns of the Sanders administration was the use of Memorial Auditorium. By the end of the 1970s, the auditorium had become a drain on taxpayers. Paquette’s administration had complicated matters further by prohibiting rock concerts in the venue following a 1977 clash between police and concert-goers. In 1980, Memorial Auditorium operated at a loss—the $23,000 in rental revenue collected that year failed to cover even the building’s $28,000 heating bill. The following December, Driscoll submitted a proposal to rent out Memorial Auditorium’s basement to the Ethan Allen Child Care Center.[6] But controversy soon followed.

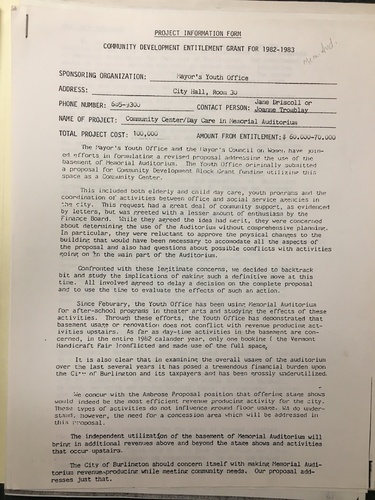

Under Driscoll’s proposal, the city would not rent the space out directly to the day-care center. Instead, her plan called for the city to rent the auditorium’s basement to the Memorial Auditorium Conversion Committee—a private group, with no official status, of which Driscoll was a member. This committee, in turn, would rent the space to the day-care center. Driscoll’s plan was to be supported by a first-year budget in excess of $45,000, which would be provided to the Memorial Auditorium Conversion Committee by the city government through its Community Development Funds. That budget would be used to hire a full-time employee to manage the basement—though the city at the time already had set in motion a plan to hire a manager for the entire building. Furthermore, the basement manager—though hired with the city’s money—would not be a city employee, but rather accountable to the Conversion Committee’s board of directors. Only twenty percent of the generated revenue would go back to City Hall; ten percent would be paid to the basement manager as commission on top of salary, and the rest would go back into programming. In addition, the Conversion Committee would not have to pay rent for the first six months of the lease.[7]

Driscoll’s proposal did not move forward, though she continued her efforts to turn the space into a day-care and community center. In June 1983, Sanders recommended a $21,000 salary for Driscoll, to be paid with federal community development block grants. The youth office’s annual budget, in turn, would be raised from $9,800 to $30,000.[8]

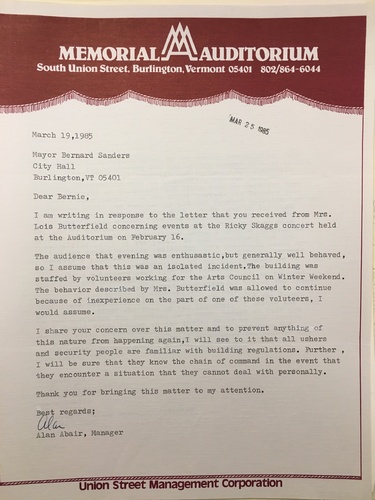

As the debate surrounding the day-care center continued, the youth office used Memorial Auditorium as the focal point of their community outreach. Between 1981 and 1984, the auditorium hosted circus skill workshops, a musical, an after-school program, and an international exchange summer camp.[9] Still, the youth office continued to operate against a background of unbridled controversy. In early March 1984, within days of the city election, the Mayor’s Youth Office published the first issue of the Queen City Special—a youth-run monthly newspaper, written and produced in the basement of Memorial Auditorium.[10] Most of the newspaper’s staff was between the ages of fourteen and sixteen, though some began working on it while in the seventh or eighth grade. Objections, both the warranted and the inordinate variety, were quick to surface: While the newspaper was ostensibly apolitical, in practice it was far from it; the March-April edition contained editorials on civil disobedience and school prayer, the latter of which concluded that President Reagan was “disrupting the country with his reactionary reasoning.”[11] Moreover, and far more importantly, the Queen City Special accepted advertisements, thereby entering into direct competition with the tax-paying newspapers that financed it. Regardless of the validity of these objections, the fact remains—with a circulation of around 7,000 through public schools and the weekly Vanguard Press distribution points, the Queen City Special was no child’s play.[12]

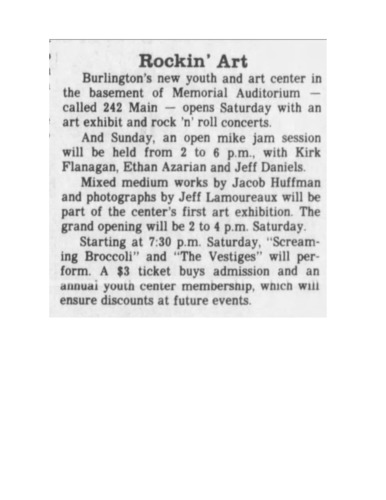

In 1984, the youth office launched plans to create a teen center. The Neighborhood Planning Assembly representatives, who controlled CDBG funding priorities, opposed the project. A survey in the Queen City Special indicated that the city’s youth wanted it.[13] With Sanders’ support, the teen center received CDBG funding in 1985.[14] The teen center was built in the basement of Memorial Auditorium, and in 1986 changed its name to 242 Main.[15] The new teen center flourished, and by 1987 even had its own public-access television show.[16]

The Mayor’s Youth Office provided a chance for Burlington’s youth to develop a voice in their community. Controversies aside, the actions of the Youth Office were successful in addressing the needs of low- and moderate-income families—particularly through its role in the debate surrounding day-care. At the same time, the Mayor’s Youth Office can largely be seen as a microcosm for some of the difficulties faced by the Sanders administration. The strong opposition and outright vitriol faced by Jane Driscoll and the Youth Office—especially during Sanders’ first term—mirrors the Democratic and City Hall obstructionism faced by the Sanders administration in its early years.

Sources

[1] “Sanders Stuns Paquette in Close Mayoral Race,” Burlington Free Press, 4 March 1981.

[2] Greg Guma, The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution (South Burlington, Vermont: New England Press, 1989), 19-42.

[3] “Sanders Mayoralty Would Have to Deliver Promises,” Burlington Free Press, 5 March 1981.

[4] “Sanders Wants Advisory Board to Take Over Youth Activities,” Burlington Free Press, 7 June 1981.

[5] “Program to Organize City’s Youths,” Burlington Free Press, 24 June 1981; “Youth Director Driscoll Balances Her Ties to Mayor, Individuality,” Burlington Free Press, 20 July 1981; “Youth Office Opened in City Hall,” Burlington Free Press, 30 July 1981.

[6] “Mahoney Wants to Increase Use of Memorial Auditorium,” Burlington Free Press, 29 July 1981; “Auditorium’s Use May Be Changed,” Burlington Free Press, 1 December 1981.

[7] “Hidden Aspects of Day Care Plan Demand Scrutiny,” Burlington Free Press, 4 January 1982.

[8] “Burlington Gets More Development Money,” Burlington Free Press, 20 April 1983; “Grant Expenditures Undecided,” Burlington Free Press, 22 June 1983; “Driscoll’s Special Status of Concern to Some Aldermen,” Burlington Free Press, 27 June 1983; “Role of Youth Office Aide Merited Closer Examination,” Burlington Free Press, 28 June 1983; “Sanders Staffs Empire in City Hall With Friends,” Burlington Free Press, 3 July 1983.

[9] “Burlington Hosts ‘People’s Circus,’” Burlington Free Press, 24 June 1981; “Kids of Burlington Become Orphans,” Burlington Free Press, 3 December 1981; “After School Program,” Burlington Free Press, 4 May 1983; “International Students Put Stress on Understanding,” Burlington Free Press, 22 July 1984.

[10] “Mayor’s Youth Office Should Not Be in Newspaper Business,” Burlington Free Press, 12 March 1984; “Setting it Straight,” Burlington Free Press, 13 March 1984.

[11] “Editorial,” Queen City Special (March-April).

[12] Steven Soifer, The Socialist Mayor: Bernard Sanders in Burlington Vermont (Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1989), 185.

[13] Soifer, The Socialist Mayor, 185.

[14] “Need for New Downtown Youth Center Questioned,” Burlington Free Press, 23 May 1985.

[15] “Rockin’ Art,” Burlington Free Press, 21 March 1986; “242 Main,” Burlington Free Press, 29 March 1986

[16] “Teens Have a Place to Call their Own,” Burlington Free Press, 1987.